Mountain Themes - Rings Earrings Bracelets Pendant Necklaces

Bolo Tie – Bola Tie – Which is correct?

Many refer to the western tie as a bolo tie, but this Arizona Highways (Vol 74, 1998) article by Don Dedera begs to differ.

You can find my Bolos plus buckles and cuff links on my etsy – at this link https://www.etsy.com/shop/JewelryAndStoneArt?ref=search_shop_redirect§ion_id=31852917

“Arizona Highways” Publication date thought to be 1998 Vol 74 pg 49

“Love It or Leave It, but Please Don’t Call It a Bolo Tie” by DON DEDRA

Arizona is the only member of the Union to have by law designated a state necktie. I think so. Let another state with an official style of neckwear prove me wrong. True, in certain more proper locales such as Boston and San Francisco, it appears to be illegal to wear any cloth pattern but diagonal stripes. But the custom is not imbedded in statute.

For Arizona, there’s a law. In the state where it was born, the many faceted bola by legislative act and gubernatorial approval is an icon equated to the customary state flag, flower, bird, and tree (they being, respectively: setting sun-copper star, saguaro blossom, cactus wren, and paloverde.

One day in the late 1940s, Victor E. CedarstafT of Wickenburg, Arizona, was chasing a wild horse when his hat blew off. Afraid he might lose his fancy silver-mounted hatband, Cedarstaff hung it around his neck. Immediately a companion took notice, and said, “Nice tie you’ve got there, Vic.” Voila. Being an accomplished metalsmith and leatherworker, Cedarstaff transformed his inspiration into a string of braided calfskin, tipped with silver globes and threaded through a slide of silver and turquoise.

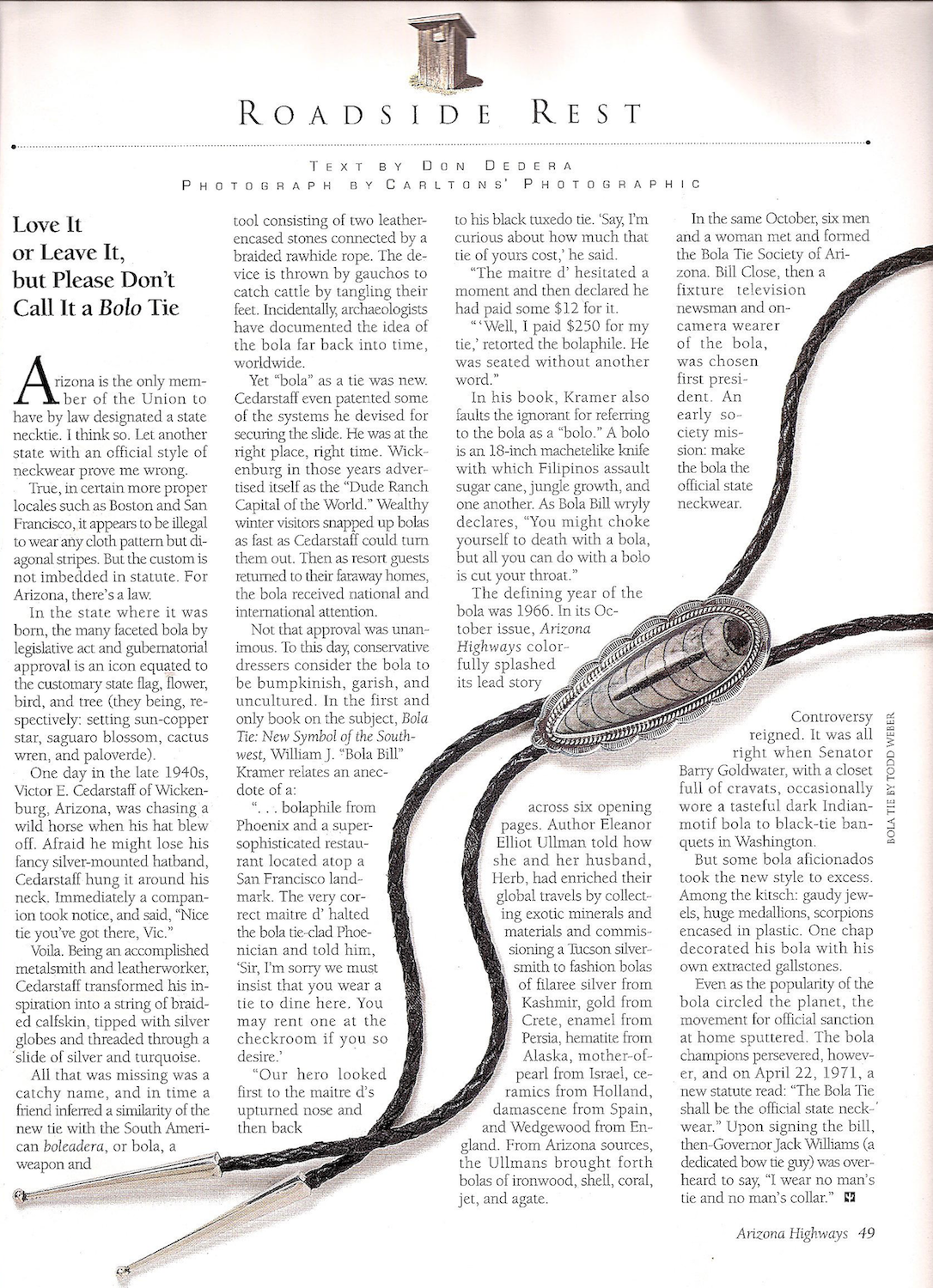

All that was missing was a catchy name, and in time a friend inferred a similarity of the new tie with the South American boleadera, or bola, a weapon and tool consisting of two leather encased stones connected by a braided rawhide rope. The device is thrown by gauchos to catch cattle by tangling their feet. Incidentally, archaeologists have documented the idea of the bola far back into time, worldwide.

Yet “bola” as a tie was new. CedarstafT even patented some of the systems he devised for securing the slide. He was at the right place, right time. Wickenburg in those years advertised itself as the “Dude Ranch Capital of the World.” Wealthy winter visitors snapped up bolas as fast as Cedarstaff could turn them out. Then as resort guests returned to their faraway homes, the bola received national and international attention. Not that approval was unanimous.

To this day, conservative dressers consider the bola to be bumpkinish, garish, and uncultured. In the first and only book on the subject, Bola Tie: New Symbol of the Southwest, William J. “Bola Bill” Kramer relates an anecdote of a: ” … bolaphile from Phoenix and a super sophisticated restaurant located atop a San Francisco landmark.

The very correct maitre d’ halted the bola tie-clad Phoenician and told him, ‘Sir, I’m sorry we must insist that you wear a tie to dine here. You may rent one at the checkroom if you so desire. “Our hero looked first to the maitre d’s upturned nose and then back to his black tuxedo tie. ‘Say, I’m curious about how much that tie of yours cost, he said. “The maitre d’ hesitated a moment and then declared he had paid some $12 for it. “‘Well, I paid $250 for my tie,’ retorted the bolaphile. He was seated without another word.”

In his book, Kramer also faults the ignorant for referring to the bola as a “bolo.” A bolo is an 18-inch machete like knife with which Filipinos assault sugar cane, jungle growth, and one another. As Bola Bill wryly declares, “You might choke yourself to death with a bola, but all you can do with a bolo is cut your throat.”

The defining year of the bola was 1966. In its October issue, Arizona Highways colorfully splashed its lead story across six opening pages. Author Eleanor Elliot Ullman told how she and her husband, Herb, had enriched their global travels by collecting exotic minerals and materials and commissioning a Tucson silver smith to fashion bolas of filagree silver from Kashmir, gold from Crete, enamel from Persia, hematite from Alaska, mother-of pearl from Israel, ceramics from Holland, damascene from Spain, and Wedgewood from England. From Arizona sources, the Ullmans brought forth bolas of ironwood, shell, coral, jet, and agate.

In the same October, six men and a woman met and formed the Bola Tie Society of Arizona. Bill Close, then a fixture television newsman and on camera wearer of the bola, was chosen first president. An early society mission: make the bola the official state neckwear. Controversy reigned. It was all right when Senator Barry Goldwater, with a closet full of cravats, occasionally wore a tasteful dark Indian-motif bola to black-tie events in Washington. But some bola aficionados took the new style to excess. Among the kitsch: gaudy jewels, huge medallions, scorpions encased in plastic. One chap decorated his bola with his own extracted gallstones.

Even as the popularity of the bola circled the planet, the movement for official sanction at home sputtered. The bola champions persevered, however, and on April 22, 1971, a new statute read: ‘The Bola Tie shall be the official state neck-wear.” Upon signing the bill, then-Governor Jack Williams (a dedicated bow tie guy) was overheard to say, “I wear no man’s tie and no man’s collar.”